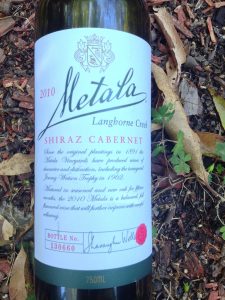

Metala Langhorne Creek Shiraz Cabernet 2010

Metala Langhorne Creek Shiraz Cabernet 2010

Apple iPhone 4s, builtin 4.28mm (~35mm) lens, 1/60 sec, f/2.4, ISO 50.

In vino veritas … but is there? I suspect the saying simply refers to wine’s infamous ability to loosen tongues, and that is not what interests us here. Wine, however, has its own truth, which is unrelated to the unguarded confidences of inebriates, that is perhaps universal and eternal precisely because it is so local and specific.

You might be seeing the idea that I’m dancing around here. Great wine reflects where and when the grapes were grown as much, if not more, than what happened to it once they got to the winery. They reflect the weather of the growing season, and the climate, soil, and aspect of their vineyard — or vineyards. (Must the impact of terroir be more dilute in wines made with grapes from a number of different vineyards within the same region? Or, even, from different regions?). As Henri Jayer said, “Vines each have typical aromas, small red and black berries and cherry for pinot, which can be found regardless of the region of production, but terroirs develop the potential of that extraordinary and still mysterious vine” (Rigaux 2009, p. 148).

That winemaking will have an impact is inevitable — grapes do not turn into good wine by themselves. Different techniques in the winery, and choice of oak barrels (or no oak barrels) will all have their impacts. But, hopefully, not enough to drown out the rather quiet voice of the terroir. Good winemaking may be about growing (or purchasing) good grapes and not messing them up in the winery, but there’s more to ‘not messing up’ than such a simple sentence implies!

All of this is a roundabout way to saying that great wine will reflect where it is grown, and this may lead to wines which are truthful to their site, but idiosyncratic. The wine pictured is a Shiraz-Cabernet blend from Langhorne Creek in South Australia. It is a big wine — full of the “muddy soulfulness of the Creek”, and the “eucalypt-and-mudcake” character that Philip White described as typical of the wine (White 2013); deep and opaque in colour, and 15% alcohol — and thus, perhaps, seems as far away from, say, a Jura Poulsard as one could get whilst still being a red wine. Yet, if each reflects where it was grown with some honesty, they could both be said to be true wines, great wines. They reflect the radically different sites in which they were grown. As Henri Jayer said, “From all this we should learn that typicity exists, that it shows itself in extraordinarily diverse ways, and we must respect that” (Rigaux 2009, p. 49).

None of this is to erase the individual preferences of whoever ends up drinking the stuff, of course. It’s possible someone more accustomed to Bordeaux, Burgundy and the Loire may not enjoy such a massive, full-bodied wine as the Metala. Or that someone who likes such wines may not like lighter reds. (Personally, I like both…). But is it possible to say that, whilst you don’t like the wine style, it is a true reflection of its terroir? And can a wine which is not from a great site be a true wine but not a great wine? As Jayer said, “When we taste a wine, we taste to see whether it has good typicity, and if it illustrates the general characteristics of its terroir ” (Rigaux 2009, p. 46).

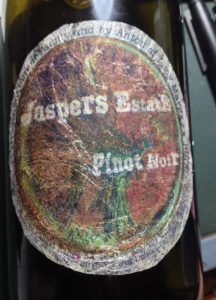

Lucy Margaux Vineyards Jaspers Estate Pinot Noir 2015

Lucy Margaux Vineyards Jaspers Estate Pinot Noir 2015

Apple iPhone 4s, builtin 4.28mm (~35mm) lens, 1/20 sec, f/2.4, ISO 80.

Rigaux, J 2009, A Tribute to the Great Wines of Burgundy: Henri Jayer, Winemaker from Vosne-Romanée, trans. JK Finkel, Terre en Vues, Le Chatelet, France.

White, P 2013, Jimmy Watson Tropy Goes To a Wine, viewed 4/12/2016, <http://drinkster.blogspot.com/2013/01/jimmy-watson-trophy-goes-to-wine.html>.

Discover more from vinomadefied ramblings

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.