Pommard from the vineyards, 27th September 2013

Pommard from the vineyards, 27th September 2013

Pentax K-x, 18-125 mm lens @ 73 mm, 1/125 sec, f/8.0, ISO 200.

Some places you can’t forget. They bury themselves deep within you, and refuse to leave. Everything else is seen in relation to them – for better, or worse. I grew up in London, and the brilliant blue of a clear winter’s day, or the oppressively leaden sky of a dismal summer day, is always with me.

One such place, for me, has been Burgundy. For one reason or another, I have always visited in late August or early September. Arriving by train, from London via Paris, you first notice how Burgundy still clings to summer, even as London sidles towards the grey drizzle of winter. Changing trains in Dijon, the local train to Beaune – historically, the wine producing capital of the region, where the major wineries had their bases – local stations and vineyards flash by, as well as woodland and cornfields.

Once in Beaune, it’s hard to know what to do. Most of the famous wineries require appointments, or are outside Beaune itself, in the smaller villages, in the cellars of medieval houses, or in concrete warehouses on the edge of the vineyards. Still, as Mike Steinberger said, “there may be different paths to wine geekdom, but they ultimately all converge in the same place—Place Carnot” – so you may as well head straight there. Place Carnot is, more or less, the main square of Beaune: its heart, and its centre. If nothing else, there are bistros and restaurants, and beautiful cakes at Dix Carnot.

This little square surrounds a small park; the tall buildings seem quintessentially French. Just a street off to one side is the Hospice de Beaune, often also called the Hôtel Dieu, with its elaborately decorated roofs made from coloured tiles. Once I’m sat outside Dix Carnot with some improbably elaborate cake, I know I’ve arrived. I can plan: what wineries to visit? Hire a car? A bike? (Yes, many of the villages south of Beaune are within comfortable cycling distance; to branch out further afield and see forests and monasteries, or even just the villages north of Beaune, a car is essential).

Frankly, Burgundy is a maze, and it will take you time to get your bearings. Take the time. Visit again. You will. I feel I am, slowly. For whatever reason, I have only visited in late summer or early autumn. I would love to see the Côte d’Or blanketed under drifts of snow, or with the first buds of spring just breaking. It is a tapestry of ancient villages and tiny vineyards, each with its own subtly different aspect on the hillside, its own soil, its own climate. Vineyards just next to each other can produce profoundly different wines.

The whole region itself teeters on the edge of several climatic zones: it is part continental, part oceanic, with warm weather sometimes coming up from Provence in the south, and cold from Germany or Switzerland in the north. Even the buildings, and the towns, can start to look Provençal at times, at others, they seem northern. Burgundy is a paradox, but a delightfully vinous one.

Cycling south out of Beaune, there are small roads that wind through the vineyards towards the village of Pommard. These roads are shared only with vineyard traffic, they are ideal for cycling. You cycle past stone-wall circled vineyards, the roadside edged with wildflowers. The track meanders on towards Volnay, then Meursault, and onwards towards Chassagne-Montrachet. I have never made it further south than Meursault, so far.

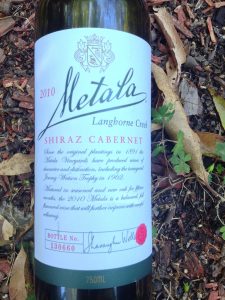

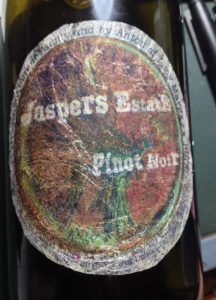

If you know something about French wines, these are names to conjure with. Pommard is known for robust, tannic Pinot Noir, its neighbour Volnay conversely for ethereal, light, perfumed Pinot. Meursault is known for its Chardonnay. Even without an appointment there are small wineries with cellar doors you can visit. Most will have wines from a range of villages, and it is instructive to taste a couple. Even where winemaking techniques are the same, the flavours and aromas differ dramatically between villages.

A place like Burgundy leaves you with many impressions, as you encounter different faces at different times. Looking back through my notes, I encounter everything from pages and pages of detail on viticultural techniques, to gripes about the weather, plans that have gone wrong, or meals that were more than memorable. Like, being forced into a small restaurant on the edge of Pommard for an unplanned lunch by unexpected rain: an inconvenience at the time, particularly since I was counting my pennies, but the sort of thing I would normally dream of. Or a meal at a small restaurant just outside the city centre of Beaune, with a shared, long table, where I ended up in deep discussion with several other diners, and did not stumble out the door until eleven pm. There were people from Japan, from Brazil, from Switzerland, from Holland, from America – and me, from Australia, via Britain. The Brazilians thought that the Europeans worked too hard, and didn’t live enough – something the Europeans objected to.

The conversation spilled out onto the street outside, and, in my head at least, followed me home. What does it say when you meet people you feel you’ve known all your life, but know you won’t meet them again? Such is travel, I guess.

The next morning, Beaune was as quiet as ever. That morning, I drove to Château-Chalon, leaving Burgundy behind for the foothills of the Alps. But, as always, I knew I’d be back.

Clos de Lambray, Morey-Saint-Denis, Côte de Nuits, 27th September 2013

Clos de Lambray, Morey-Saint-Denis, Côte de Nuits, 27th September 2013

Pentax K-x, 18-125 mm lens @ 40 mm, 1/100 sec, f/8.0, ISO 100.

This is a longer form of an essay I wrote for a travel writing competition (which I didn’t win!), organised by travel insurance company World Nomads. The version submitted can be seen here.