One reason that Italian wines are a constant source of interest for wine enthusiasts1 is that, pretty much no matter how long you’ve been studying wine, you’ll always keep coming across new regions and new grapes you’ve not heard of previously. This can happen when visiting a supermarket, or when travelling — particularly in regions not known for their wine.

For me, at least, Lombardy is such a region. I’m not sure why. It does grow quite a bit of wine, and some regions, such as Valtellina, are not particularly obscure. I guess it lacks any ‘big names’ — there is no village with the stature or recognition of Barolo or Brunello here. But — thankfully — that’s not all there is to wine.

I’ve been lucky enough to visit Brescia and Bergamo a number of times, and have enjoyed finding out about the wines grown in their respective regions. With the exception of Franciacorta sparkling wine, which I won’t cover here, neither are terribly well known outside the region, but both are — to my mind — well worth exploring. I’ll quickly run through a few of the regions I’ve come across so far, and give some details of the wines I’ve tried.

Brescia

Brescia’s vineyards sit between the mountains and the plain, with Alpine breezes on one side and warm Po Valley sunshine on the other. These are the same hills that give the world Franciacorta sparkling wine, but the still wines deserve a little attention too. Curtefranca DOC covers much of the same ground, and the soils are a patchwork — limestone and marl here, glacial debris there — all of which helps keep the wines lively. The reds lean on Bordeaux grapes like ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and ‘Merlot’, often with an Italian twist from ‘Nebbiolo’ or ‘Barbera’, while the whites are typically ‘Chardonnay’ and ‘Pinot bianco’.

One curiosity worth mentioning is the Pusterla vineyard, Europe’s largest urban vineyard, which clings to the slopes just below Brescia’s castle. This sun-exposed hillside is the top of a stratified limestone spur, and is known for its marl and flint nodules, also called medolo. First planted in 1037 by the royal monastery of Santa Giulia, the site has undergone many changes of ownership over the centuries and has been abandoned at various points. Despite its difficult history, it is now thriving again under the care of Emanuele Rabotti (Monte Rossa winery, Franciacorta). This unique vineyard is home to a unique grape — ‘Invernenga’, a rare late-ripening white with unusually thick, polyphenol-rich 🦜 skins. Once grown mostly for passito, it now makes dry whites with a pleasantly savoury edge — a little slice of vineyard history hidden in the city.

If you follow the vines south, you come to Montenetto di Brescia IGT, centred on Monte Netto, a clay-rich rise out of the plain. Viticulture here likely started with the Romans, once the marshy soils had been drained, but the first definite reference to wine growing in the region was in the sixteenth century, with Le dieci giornate della vera agricoltura e dei piaceri della villa by Agostino Gallo, Renaissance agronomist, which mentions ‘Marzemino’ in particular, now grown as Capriano del Colle DOC Marzemino. The IGT rules are broad, but the standouts are ‘Trebbiano’ in its various guises and ‘Marzemino’, alongside ‘Barbera’, ‘Sangiovese’, ‘Merlot’, and ‘Chardonnay’. The whites tend to be floral and lightly fruity, while the reds are fresh and harmonious — the sort of bottles made for local trattoria cooking rather than long-term cellaring.

Curtefranca DOC

2020 Ferghettina Curtefranca

Colour: Medium(+) purple

Nose: medium(-) intensity, tertiary, developing. Redcurrant, cassis, strawberry, pomegranate, cherry syrup. Blueberry. Mushroom, barnyard, forest floor, cough syrup. Cedar, sweet spice.

Palate: dry, medium(+) acidity, medium tannins, medium alcohol (13,5%), medium bodied. Medium length finish, medium intensity. Redcurrant, cassis, strawberry, pomegranate, cherry syrup. Blueberry. Mushroom, barnyard, forest floor, cough syrup. Cedar, sweet spice.

Conclusions: very good. Can drink now, but suited to further ageing.

Seal: cork

Blend: 50% Cabernet Sauvignon, 30% Merlot, 10% Nebbiolo, 10% Barbera – I am not sure if this varies somewhat from year to year

Tasted 17/2/2023

2022 Ferghettina Curtefranca

Colour: medium (+) purple

Nose: medium(-) intensity, secondary, youthful. Red and black plum, blackcurrant, fruiti di bosco jam, blueberry. Smoke, bergamot. Charred oak.

Palate: dry, medium acidity, medium tannins, medium alcohol (13,5%), medium bodied. Medium intensity, medium length finish. Red and black plum, blackcurrant, fruiti di bosco jam, blueberry. Smoke, bergamot. Charred oak.

Conclusions: good — but not as interesting as I remember from last time. P&P (pop&pour), not decanted.

Half bottle at Ma!Osteria Brescia

Tasted 23/8/2025

2019 Ca’ del Bosco ‘Corte del Lupo’ Curtefranca

Colour: medium(+) ruby

Nose: medium intensity, secondary, youthful. Pomegranate (esp. on first opening), red cherry, blueberry. Strawberries stewed in balsamic vinegar. Cedar, cinnamon, maybe vanilla. Dried herbs. Touch of earthiness. Pomegranate seemed most dominant when first opened, but blueberry came to the fore with air.

Palate: dry, medium(+) acidity, medium(+) tannins, medium alcohol (13%), medium bodied. Medium intensity, medium(+) length finish. Pomegranate (esp. on first opening), red cherry, blueberry. Strawberries stewed in balsamic vinegar. Cedar, cinnamon, maybe vanilla. Dried herbs. Touch of earthiness.

Conclusions: very good. Quite lithe and elegant, refined but with an earthy savouriness. Can drink now, but likely suited to further ageing. Just as good on day 2, after being left open overnight.

Seal: natural cork

49% Merlot, 31% Cabernet Sauvignon, 9% Cabernet Franc, 11% Carménère

Tasted 15/4/2023

2018 Coop Vitivinicola Cellatica Gussago Curtefranca Rosso

Colour: medium garnet

Nose: medium(+) intensity, tertiary, developing. Red and black plum, plum jam, bramble, cassis. Tamarillo. Black pepper, tomato stem. Some savoury character and maybe the start of forest floor character.

Palate: dry, medium acidity, medium(+) tannins, medium alcohol (13%), medium bodied. Medium intensity, short finish. Red and black plum, plum jam, bramble, cassis. Tamarillo. Black pepper, tomato stem. Some savoury character and maybe the start of forest floor character.

Conclusions: good — let down slightly by the short finish. Can drink now, but suited to further ageing. P&P (pop&pour), not decanted.

Seal: DIAM2 cork

Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon.

Tasted 21/5/2024

2015 Ricci Curbastro ‘Vigna Santella del Gröm’ Curtefranca

Colour: medium(+) ruby

Nose: medium(+) intensity, secondary, youthful. Strawberry, redcurrant, red and black plum. Blackcurrant jelly? Strawberry jam? Blueberry. White pepper, cedar, nutmeg, bread dough. Smoke and maybe bergamot.

Palate: dry, medium(+) tannins (fine grained, silky, but drying), medium acidity, medium alcohol (12,5%), medium(-) bodied. Strawberry, redcurrant, red and black plum. Blackcurrant jelly? Blueberry. White pepper, cedar, nutmeg. Cough syrup/medicinal. Bergamot?

Conclusions: very good. Can drink now, but suited to further ageing. Quite fresh and young at eight years of age. Relatively light and dominated by red fruit. The tannins and acidity work well with food. Very drinkable.

Blend of Cabernet Franc, Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, Carmenere, and Barbera.

Tasted 7/11/2023

2021 Ferghettina Curtefranca Bianco

Colour: pale lemon-green

Nose: medium intensity, secondary, youthful. Green apple, lemon, lemon peel. Pineapple. Nectarine. Honey. White flowers. Lees character: biscuit and cream.

Palate: dry, medium(+) acidity, medium alcohol (12,5%), medium(-) bodied. Medium intensity, medium long finish. Green apple, lemon, lemon peel. Pineapple. Nectarine. Honey. White flowers. Lees character: biscuit and cream. Green apple very dominant when first opened, but improves with air.

Conclusions: good. Can drink now, but suited to further ageing. Pretty good value at €9.50!

Seal: technical cork.

DAY2: left in fridge overnight. Green apple and nectarine still prominent, but now maybe with wet stone and saline notes.

80% Chardonnay 20% Pinot Blanc (Pinot Bianco)

Tasted 6/6/2023

Montenetto di Brescia IGT

2021 Barone Pizzini Montenetto di Brescia IGT

Colour: pale lemon yellow

Nose: medium intensity, secondary, youthful. Lemon, lemon peel. Apple — Granny Smith, Russet. White flowers. Cream?

Palate: dry, high acidity, medium alcohol (13%), medium bodied. Medium intensity, medium length finish. Lemon, lemon peel. Apple — Granny Smith, Russet. White flowers. Cream?

Conclusions: good. Can drink now, but suited to further ageing. P&P (pop&pour), not decanted.

Seal: DIAM5 technical cork

Blend of Trebbiano & Chardonnay

Tasted 18/8/2024

Vino di Tavola (Pusterla vineyard, Brescia)

2020 Monte Rossa Pusterla Vino Bianco

Colour: medium gold

Nose: medium intensity, secondary, youthful. Dried apricot, lemon, lemon peel, underripe pineapple. Heritage apples. Honeyed. Almonds? Ginger? Wet stone, saline. Hay.

Palate: dry, medium(+) acidity, medium alcohol (12%), medium(-) bodied. Dried apricot, lemon, lemon peel, underripe pineapple, kiwifruit. Heritage apples. Honeyed. Ginger? Wet stone, saline.

Conclusions: very good. I wasn’t expecting much from this for whatever reason — I worried it might just be a novelty — but it’s a genuinely interesting, complex, and unusual wine. Hard to pin down the flavours and aromas precisely. 100% late harvest Invernenga, an autochthonous grape cultivar from Brescia, Lombardy, Italy, and grown in a vineyard within the castle grounds of Brescia — said to be the largest urban vineyard in Europe. P&P (pop&pour), not decanted.

Seal: screwcap.

Tasted 2/5/2024

Bergamo

Bergamo also boasts a long relationship with the vine. The Romans planted vineyards around Scanzorosciate, and the region was well regarded enough for its wine that the village of San Lorenzo had a temple to Bacchus. The Lombard invasions set viticulture back, but monasteries kept the culture of the vines alive, and by the fifteenth century Bergamo’s wines were pouring into Milan. Like elsewhere, phylloxera caused devastation, but early twentieth-century replantings set the stage for the region’s modern revival.

The creation of the Valcalepio DOC in 1976 was a key moment for the modern history of wine growing in Bergamo. The DOC covers the hills between the Orobic Alps, Lake Iseo, and Monte Canto. The reds are usually Bordeaux blends — a bold choice at the time — ‘Merlot’ with ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’, occasionally scented with the local ‘Moscato di Scanzo’. The whites draw on ‘Chardonnay’, ‘Pinot bianco’, and ‘Pinot grigio’. They’re good food wines, often with a savoury edge that suits the region’s hearty cooking. In 1993, a Valcalepio rosso riserva DOC was created, allowing for the production of longer-aged wines. Also worth noting: a passito made from ‘Moscato di Scanzo’, made locally since at least 1347, is said to have been a favourite of Catherine the Great. (I’ve yet to try this myself… even in Italy, the wines from here can be a bit tricky to find!)

Terre del Colleoni DOC, a newer denomination (2011), takes in a broader cast of grapes: ‘Schiava’, ‘Marzemino’, ‘Franconia’, and the rare ‘Incrocio Terzi’, along with ‘Manzoni bianco’. These wines tend to be fruit-forward and easy to enjoy, from pale, cherry-coloured reds to aromatic whites with citrus and stone-fruit lift. To my mind, it’s when you add in the tiny appellations such as Moscato di Scanzo DOCG — a sweet red made from the native grape of the same name — that Bergamo’s picture comes fully into focus, making it far more interesting than its low profile might suggest.

And that, really, is the point: neither Brescia nor Bergamo may be household names in the wine world, but both reward a little curiosity — and a bottle or two shared2 at the table.

Valcalepio DOC

2020 Locatelli Caffi Valcalepio

Colour: medium (-) purple

Nose: medium (-) intensity, secondary, youthful. Cassis, red plum, red cherry, pomegranate. Cola. Blackcurrant leaf, maybe green capsicum? Sweet spice. Earthy, forest floor

Palate: dry, medium acidity, medium tannins, medium alcohol)13%), medium bodied. Medium (-) intensity , medium(-) length finish. Cassis, red plum, red cherry, pomegranate. Cola. Blackcurrant leaf, maybe green capsicum? Sweet spice. Earthy, forest floor

Conclusions: good. Can drink now but suited to further ageing

Seal cork. Merlot – Cabernet blend.

Notes from half bottle at Da Ornella, Bergamo

Tasted 2/6/2023

2023 Locatelli Caffi Valcalepio

Colour: medium ruby

Nose: medium(-) intensity, secondary, youthful. Red plum, blackcurrant. Strawberry, redcurrant. Gooseberry, green capsicum. Sweet spice.

Palate: dry, medium(-) tannins, medium alcohol (13,5%), medium acidity, medium bodied. Red plum, blackcurrant. redcurrant. Gooseberry, green capsicum. Sweet spice.

Conclusions: good – just a little short on the palate. Can drink now, but suited to further ageing. P&P (pop&pour), not decanted.

Half bottle at Trattoria da Ornella, Bergamo.

Tasted 26/8/2025

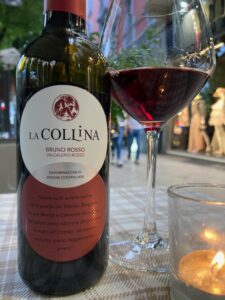

2018 La Collina ‘Bruno’ Valcalepio Rosso

Colour: medium(-) ruby

Nose: medium intensity, secondary, youthful. Fruits of the forest: strawberry, blueberries, blackberry, blackcurrant, redcurrant. Hint of forest floor? With air, dried orange peel. Vanilla, cedar.

Palate: dry, medium(-) acidity, medium(-) tannins (v.smooth & fine grained), medium alcohol (13,5%), medium(-) bodied. Medium intensity, medium length finish. Fruits of the forest: strawberry, blueberries, blackberry, blackcurrant, redcurrant. Hint of forest floor? With air, dried orange peel. Vanilla, cedar.

Conclusions: very good. Can drink now, but suited to further ageing.

Seal: cork

Notes from half bottle at La Ciotola Restaurant, Bergamo

Tasted 3/6/2023

2018 Tenuta Castello di Grumello Valcalepio

Colour: medium ruby

Nose: medium intensity, secondary, youthful. Red cherry, red and black plum, cassis. Juniper berry. Dried red fruit leather, strawberry. Rosemary? Cedar, bitter cocoa. Earthy and leathery in the empty glass.

Palate: dry, medium(-) tannins, medium(+) acidity, high alcohol (14%), medium bodied. Medium intensity, medium length finish. Red cherry, red and black plum, cassis. Juniper berry. Dried red fruit leather, strawberry. Tamarillo, cranberry. Rosemary? Cedar, bitter cocoa. Earthy and leathery.

Conclusions: very good. Can drink now, but suited to further ageing.

Seal: DIAM5 cork

Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon.

Tasted 13/11/2023

Terre del Colleoni

2021 Villa Domizia Punto ‘Uno Manzoni’ Terre del Colleoni Bianco

Passionfruit, pineapple, apricot, lemon curd. Lots of fresh tropical fruit backed up by fresh citrusy acidity. Wet stones. Quite fresh and refreshing.

No detailed notes since by the glass at a restaurant. Very good!

By the glass at La Bottega Del Gusto, Bergamo

Tasted 3/6/2023

and finally… a Franciacorta

NV Facchetti Franciacorta Franciacorta Nature

Colour: pale lemon yellow

Nose: medium(-) intensity, youthful, secondary. Lemon, lemon peel, green apple. Hint of beeswax and lanolin. Cream.

Palate: medium(+) acidity, medium alcohol, medium bodied, delicate mousse. Medium intensity, medium length finish. Lemon, lemon peel, green apple. Hint of beeswax and lanolin. Cream. Wet stone, hint of salinity.

Conclusions: very good! Can drink now, but likely suited to further ageing.

By the glass.

Tasted 23/8/2025

References

Brescia – Quattrocalici. https://www.quattrocalici.it/provincia/brescia/

Vigneto Pusterla – the terroir. https://www.vignetopusterla.com/il-terroir/

“The largest urban vineyard in Europe is in Brescia: showcasing a rare grape”, Gambrro Rosso. https://www.gamberorossointernational.com/news/the-largest-urban-vineyard-in-europe-is-in-brescia-showcasing-a-rare-grape/

Curtefranca DOC – Quattrocalici. https://www.quattrocalici.it/denominazioni/curtefranca-doc/

Montenetto di Brescia – Quattrocalici. https://www.quattrocalici.it/denominazioni/montenetto-di-brescia-igt/

Consorzio Montenetto. https://consorziomontenetto.it/index.php/montenetto/

Bergamo – Quattrocalici. https://www.quattrocalici.it/provincia/bergamo/

Valcalepio DOC – Quattrocalici. https://www.quattrocalici.it/denominazioni/valcalepio-doc/

Valcalepio DOC – Consorzio Tutela Valcalepio. https://www.valcalepio.org/vini-tutelati/valcalepio-doc/

Moscato di Scanso – A Sprinkle of Italy. https://asprinkleofitaly.com/moscato-di-scanzo-docg/

Terre del Colleoni DOC – Quattrocalici. https://www.quattrocalici.it/denominazioni/terre-del-colleoni-o-colleoni-doc/

- I don’t really like the term ‘wine enthusiast’, perhaps due to a hazy memory of the joke about axe wielding maniacs preferring to be called axe enthusiasts. Nothing quite captures what I want to say as well as the French phrase ‘amateur de vin’. Unfortunately, the word amateur has become rather devalued in English — it is rather sad that doing something simply for the love of it is seen as a negative! ↩︎

- Well, I’ll try. Sharing is difficult, especially with good wine. ↩︎

De-stemming by hand

De-stemming by hand Murray-Darling Grenache

Murray-Darling Grenache

Fermenting must

Fermenting must